Strolling through the medieval old towns of Europe, as you gaze into the distance at…

From the Cosmos to Mortal World: The Origins and Evolution of Gold and Silver Ware in Civilization

“There are three grades of metal, with gold being the highest.” This statement from the Classic of Mountains and Seas reveals that the Chinese understanding of gold and silver dates back at least three thousand years. However, the story of gold and silver ware is far more ancient than written records.

I. Heavenly Gifts and Earthly Treasures: The Primordial Discovery of Gold and Silver

The origins of gold and silver ware began with humanity’s first encounter with these two precious metals.

Gifts of Nature:

Natural Gold: Ancient people discovered gleaming natural gold nuggets in riverbeds. The earliest gold artifacts date back to the Varna culture in Bulgaria around 5000 BCE.

Silver’s Later Emergence: As silver often exists in sulfide ores, refining techniques emerged later. The earliest silverware appeared in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) around 4000 BCE.

Earliest Evidence in China:

Gold earrings from the Xia Dynasty (around 2000 BCE) unearthed at the Yumen Huoshaogou site in Gansu.

Shang Dynasty gold foil (13th century BCE) from the Tomb of Fu Hao in Yinxu, Anyang, Henan.

The Shang Dynasty gold masks and scepters from the Sanxingdui site in Sichuan, showcasing the astonishing gold craftsmanship of the ancient Shu Kingdom.

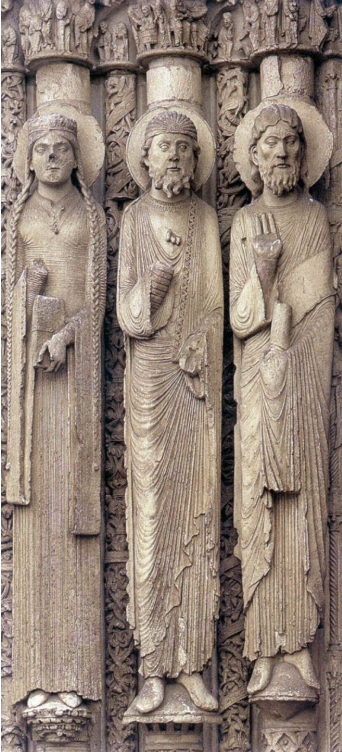

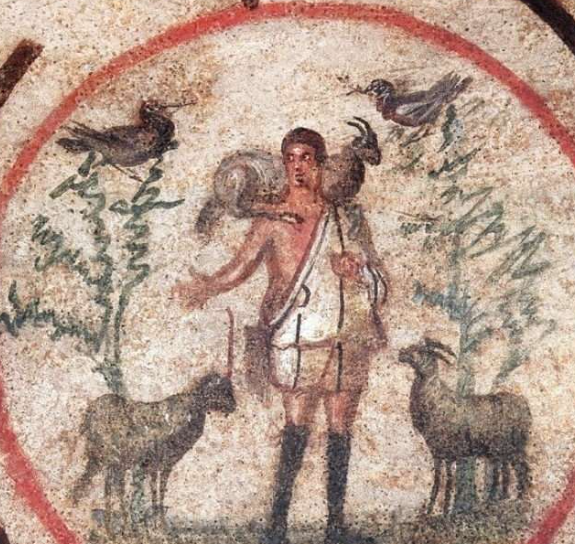

II. Sacred Origins: From Divinity to Royal Power

Initially, gold and silver were not used for daily purposes but as mediums to connect with the divine.

Sorcery and Rituals:

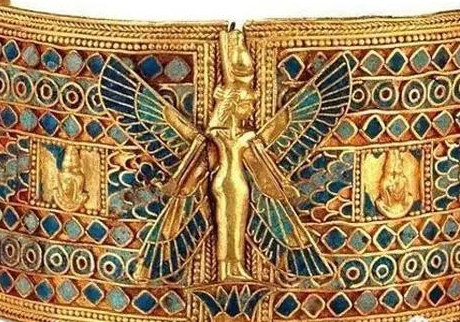

Ancient civilizations widely believed gold was “the sweat of the sun” and silver “the tears of the moon.” In ancient Egypt, pharaohs were considered incarnations of Horus, the “god of gold,” exemplified by Tutankhamun’s gold mask. In China, gold ornaments during the Shang and Zhou dynasties were primarily used in rituals or by shamans communicating with deities.

Monopoly of Royal Power:

During the Spring and Autumn period, “carriages adorned with gold and jade” became symbols of nobility. The Rites of Zhou records: “The king’s ceremonial robes are adorned with gold and jade.” Gold began transitioning from altars to thrones but remained exclusive to a select few.

III. The Awakening of Technology: A Turning Point in Forging Civilization

Gold and silver ware truly became an art form with breakthroughs in key technologies.

Gifts from the Steppe (8th–3rd Century BCE):

Northern nomadic peoples (such as the Xiongnu and Scythians) developed exquisite animal-themed gold craftsmanship, which spread to the Central Plains via the Steppe Silk Road. The Xiongnu crown discovered in Ordos, Inner Mongolia, showcases techniques like hammering, engraving, and filigree.

Imperial Melting Pot (Qin and Han Dynasties):

Emperor Qin Shi Huang unified currency, declaring “gold as the highest currency,” establishing official standards for gold ware. After Zhang Qian’s diplomatic missions to the Western Regions during the Han Dynasty, techniques like granulation and fine wirework from Central Asia were introduced to China. The gold-threaded jade burial suit of Dou Wan from the Mancheng Han tomb in Hebei, using 1.1 kilograms of gold thread, demonstrates the heights of Han Dynasty gold craftsmanship.

II. Sacred Origins: From Divinity to Royal Power

Initially, gold and silver were not used for daily purposes but as mediums to connect with the divine.

Sorcery and Rituals:

Ancient civilizations widely believed gold was “the sweat of the sun” and silver “the tears of the moon.” In ancient Egypt, pharaohs were considered incarnations of Horus, the “god of gold,” exemplified by Tutankhamun’s gold mask. In China, gold ornaments during the Shang and Zhou dynasties were primarily used in rituals or by shamans communicating with deities.

Monopoly of Royal Power:

During the Spring and Autumn period, “carriages adorned with gold and jade” became symbols of nobility. The Rites of Zhou records: “The king’s ceremonial robes are adorned with gold and jade.” Gold began transitioning from altars to thrones but remained exclusive to a select few.

III. The Awakening of Technology: A Turning Point in Forging Civilization

Gold and silver ware truly became an art form with breakthroughs in key technologies.

Gifts from the Steppe (8th–3rd Century BCE):

Northern nomadic peoples (such as the Xiongnu and Scythians) developed exquisite animal-themed gold craftsmanship, which spread to the Central Plains via the Steppe Silk Road. The Xiongnu crown discovered in Ordos, Inner Mongolia, showcases techniques like hammering, engraving, and filigree.

Imperial Melting Pot (Qin and Han Dynasties):

Emperor Qin Shi Huang unified currency, declaring “gold as the highest currency,” establishing official standards for gold ware. After Zhang Qian’s diplomatic missions to the Western Regions during the Han Dynasty, techniques like granulation and fine wirework from Central Asia were introduced to China. The gold-threaded jade burial suit of Dou Wan from the Mancheng Han tomb in Hebei, using 1.1 kilograms of gold thread, demonstrates the heights of Han Dynasty gold craftsmanship.

V. From Temple to Mortal World: The Secularization of Gold and Silver Ware

Transition in the Song Dynasty:

With the development of a commodity economy, gold and silver ware began to move beyond the imperial court. Specialized gold and silver shops emerged in Bianjing (Kaifeng), such as the “Liu Family’s Premium Aloeswood and Sandalwood Shop” depicted in the Along the River During the Qingming Festival, which also traded gold and silver ware. Forms became simpler and more practical, with motifs often conveying auspicious meanings.

Peak in the Ming and Qing Dynasties:

Ming Dynasty: The gold crown of Emperor Wanli, unearthed from the Dingling Mausoleum, was woven from extremely fine gold threads, weighing only 826 grams, showcasing unparalleled craftsmanship.

Qing Dynasty: The Imperial Workshop’s “Gold and Jade Division” gathered skilled artisans nationwide, combining gold and silver ware with enameling and gemstones to achieve extreme opulence.

Notably, private silver shops flourished during the Ming and Qing periods, bringing gold and silver ware into the homes of ordinary affluent families. “Gold and silver headdresses” in bridal trousseaus symbolized both wealth and social status.

VI. Why Gold and Silver? — The Eternal Cultural Code

Physical Properties Determine Destiny:

Immortality: Almost unreactive with any substance, remaining unchanged for millennia.

Malleability: Exceptional ductility; one gram of gold can be drawn into a wire 3 kilometers long.

Scarcity: Total global gold reserves could fill only three and a half standard swimming pools.

Accumulation of Cultural Attributes:

In Confucian culture, gold symbolizes “unwavering loyalty,” while jade represents “the virtue of a noble person.” Gold and silver ware gradually came to embody:

Symbols of power (gold seals and jade seals).

Wealth storage (gold and silver ingots).

Ritual functions (imperial rewards).

Religious sanctity (Buddha statues, ritual objects).

Blessings for life (longevity locks, full-moon gifts).

Conclusion: The Eternal Flow

From the gold earrings of the Hongshan culture to the “Golden Cup of Eternal Stability” in the Forbidden City, gold and silver ware have traversed a five-thousand-year journey in China. It began with ancient people’s reverence for natural light, flourished through artisans’ pursuit of skill, and peaked with cultural exchanges and mutual learning.

Each piece of heirloom gold and silver ware is a time capsule—preserving the aesthetics, techniques, and beliefs of its era. When we gaze upon these artifacts in museums today, we see not just the gleaming luster of metal but also how human civilization has forged natural gifts into cultural eternity.

As the Tang Dynasty poet Li Qiao wrote in his poem “Gold”:

“In southern Chu, tribute of old renown,

In western Qin, ancient cities known.

Its hue stirs springtime’s fluttering down,

Its light flows, rivaling sun and moon’s own crown.”

The immortal glow of gold and silver ware illuminates humanity’s enduring quest for beauty and eternity.