A building's facade is never a static surface. In great architecture, it's more like a…

Carved in Bones, Penned in Ink: Three Millennia of Script and Prophecy

Oracles in Cracks: Divination’s Fissures

Five thousand years ago, when an unnamed artisan carved the first intentional crack onto a turtle plastron, he likely never imagined that this single fissure would meander into a lifeblood vessel threading through the heart of Chinese civilization. The story of calligraphy begins with the scorched marks of divination, matures through the practice of daily writing, and ultimately ascends into a dance of the soul. This is not merely the natural evolution of an art form, but a protracted experiment in how humanity converses with heaven and earth.

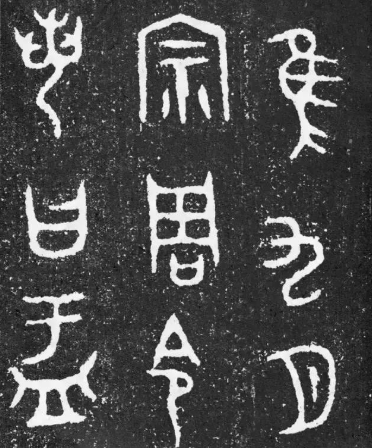

Oracle Bones: The Fissures of Divine Decree

The grand priest of the Shang king pressed a red-hot bronze probe against a turtle shell. With a faint hiss, a crack burst forth like lightning. This was not destruction, but communion—a whispered dialogue with ancestors and deities. Those early Chinese characters inscribed beside the cracks were less a record than a gloss on divine pronouncements. Each stroke was hard, direct, imbued with an unquestionable resolve. On an ox scapula unearthed at Anyang, the six characters “Guǐmǎo divination: will it rain today?” are engraved with such profound severity they seem etched into the very bones of time. Here, in this moment, calligraphy was a tremor of piety, a fingertip straining to decipher the will of heaven.

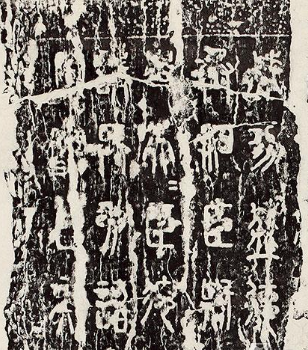

Bronze Vessels: The Weight of Power

The Zhou kings cast their military triumphs into molten bronze. As the searing metal flowed into ceramic molds, writing transcended fragile etchings to become metallic spines fused eternally with ritual vessels. The 291 seal-script characters lining the interior of the Great Yu Ding boast strokes rounded like condensed bronze, their structures as solemn as court processions. These inscriptions were destined to endure three millennia of burial—thus every stroke had to possess its own skeleton. On the ceramic molds before casting, artisans meticulously refined the edges of each character with knives. This marked the first time humans modified the form of writing for the sake of “beauty.” Here, calligraphy became the tattoo of power—an ambition to make achievement defy the corrosion of time.

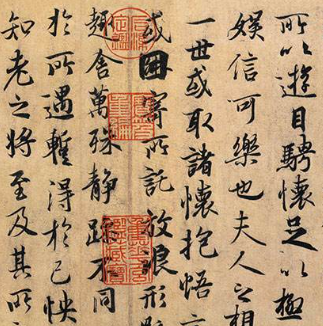

Paper: The Awakening Revelry

One day in the Eastern Han Dynasty, Cai Lun’s improved papermaking technique swept across the land. When the soft brush tip first met the resilient surface of paper, a quiet revolution began—every lift and press of the wrist, each turn and variation in speed, was infinitely magnified by this sensitive medium. After sobering up, Wang Xizhi sighed over the twenty-one corrections and revisions in his Preface to the Orchid Pavilion, unaware that these “flaws” would later be revered as expressions of raw personality. Paper liberated writing, allowing the tremors of each individual life to be preserved. In this moment, calligraphy finally broke free from the shackles of utility and began its spiritual solo dance as a pure art form.

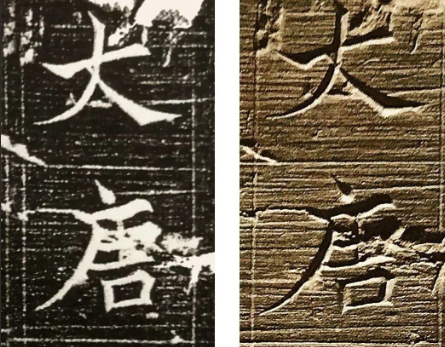

Engraved Rubbings: The Paradox of Reproduction

Emperor Taizong of the Song Dynasty oversaw the carving of the Chunhua Ge Tie, transforming masterworks of past dynasties into intaglio on jujube wood. As ink rubbings spread far and wide, scholars across the land could, for the first time, access copies of great calligraphers’ works for study. Yet the carving knife, after all, is no writing brush—stone engraving filtered away the ink’s subtle shades, the breath-like pauses of “flying white,” and the nuanced angles at which the brush tip met the paper. Even the most exquisite reproduction inevitably loses something irretrievable. Thus emerged a fascinating phenomenon: later generations copied from these rubbings, infusing their imitations with personal imagination and unintended deviations. Wang Xizhi’s original works have long vanished into dust; the “Sage of Calligraphy” we know today is, in truth, a collective phantom constructed through layers of replication. In this moment, calligraphy became a cross-temporal dance of misinterpretation and reinvention.

From Oracle Bones to the Cloud: The medium of calligraphy changes, but its essence remains—the eternal human impulse to fix flowing thought and fleeting emotion into visible traces. Whenever we lift the brush, what we write is not merely characters, but an immediate answer to the question of “how to be.”

Late at night, practicing from a model book, lamplight falls upon yuanshu paper. As I complete the final right-falling stroke of the character (eternity), I suddenly feel the brush tip traveling not only across the page—it is also carving the anxiety of divination onto turtle shells, casting the weight of authority into bronze, recording the rigor of laws on bamboo slips, and unleashing the soul’s ecstasy upon rice paper. Through this brush, three millennia of writers share with me the same breath.

The ink, still damp, resembles history just solidified. And the story of calligraphy has always been in the present continuous tense—it begins anew in every moment we lift the brush.