On the banks of the Spree River in the German capital of Berlin stands a…

Bronze Ritual Music: Echoes of Civilization Across Millennia

When we stand before the museum’s glass display cases, gazing at those time-worn yet magnificently shaped bronze vessels, we see more than mere objects—we glimpse a splendor that has been frozen in history. Though silent, they seem capable of carrying us across three millennia, back to the dawn of Chinese civilization—the Bronze Age of the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties.

I. National Treasures: Symbols of Power and Faith

Bronze—an alloy of copper with tin and lead—takes its name from the greenish patina formed by oxidation. In the history of human civilization, the emergence of bronze vessels marks a revolutionary milestone. In China, however, bronze craftsmanship reached an unparalleled artistic and technical height, distinguished by its deep integration with ritual systems, giving rise to a unique Bronze Ritual and Music Civilization.

“Of the great affairs of the state, the most important are ritual and war.”

For early dynasties, the two paramount concerns were worship and warfare, and bronze vessels served as the physical embodiment of both.

Symbols of Power:

Among all bronze forms, the ding is the most iconic. Originally a cooking vessel for boiling meat, it soon evolved into the most important ritual object. According to legend, Yu the Great cast the Nine Tripods to symbolize the Nine Provinces, and ever since, the ding has become synonymous with state authority. The Simuwu Ding (later renamed Houmuwu Ding), weighing an astonishing 832.84 kilograms, stands as the largest bronze vessel in the world. Its immense scale and imposing form silently testify to the formidable strength and supreme royal power of King Wu Ding during the Shang dynasty.

Bridging Heaven and Earth:

Bronze wine vessels (such as jue, jiao, and jia) and musical instruments (such as bianzhong bells and nao) played vital roles in rituals that connected humans with the divine. Early peoples believed that through solemn ceremonies—offering fine wine and sacrificial gifts in exquisitely crafted bronzes, accompanied by harmonious music—they could reach the ears of Heaven and seek the blessings of gods and ancestors.

II. Ingenuity and Mastery: The Fusion of Craft and Art

The casting of ancient Chinese bronzes primarily relied on the unique piece-mold casting technique. Artisans first shaped a clay model of the vessel (the “mold”), then produced outer and inner clay sections based on the model. After assembling the inner and outer molds, molten bronze was poured in. Once cooled, the molds were broken apart, revealing the finished vessel. Though seemingly cumbersome, this method produced works of astonishing precision and complexity.

The Beauty of Ornamentation:

Decoration is the very soul of bronze vessels. The taotie motif— a fierce, enigmatic animal mask— is the most iconic design. Its wide eyes and imposing presence create a powerful visual impact and spiritual aura, reflecting early beliefs in and awe of supernatural forces. Other motifs such as the kuilong dragon, phoenix bird patterns, and the yunlei (cloud-and-thunder) designs further enrich this mysterious and orderly artistic universe, forming a “theocratic aesthetic world” unique to the Bronze Age.

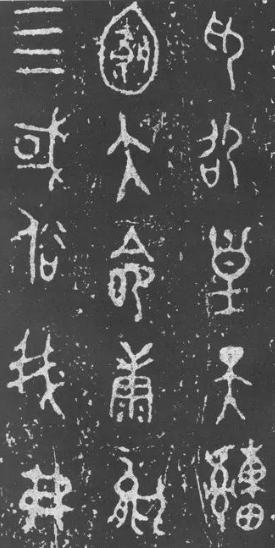

The Prestige of Inscriptions:

Bronzes of the Shang and Zhou dynasties often bear cast inscriptions, known as jinwen or zhongdingwen. These inscriptions cover a wide range of content—from records of achievements and royal bestowals to treaties, legal cases, and ancestral commemorations—serving as “history books engraved in bronze.” The 499-character inscription inside the Mao Gong Ding, the longest known bronze inscription, is of immense historical value, surpassing even the vessel itself and providing first-hand material for the study of Western Zhou history.

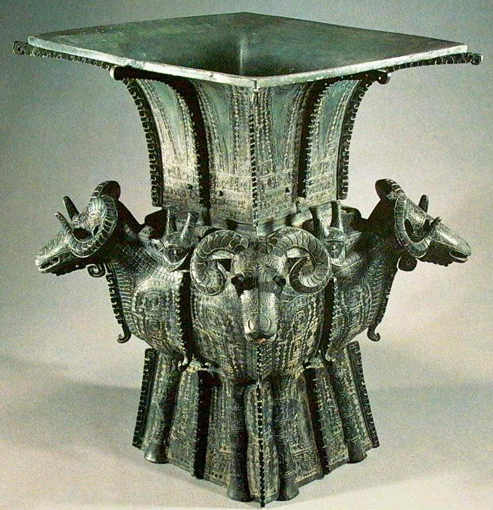

The Marvel of Form:

The shapes of bronze vessels demonstrate boundless imagination. The Four-Ram Square Zun (Siyang Fangzun) stands as a masterpiece: four horned rams are seamlessly integrated into the structure of the zun. With elegant lines, intricate construction, and the combined use of relief, line engraving, and sculpture, it represents the pinnacle of bronze craftsmanship—a perfect fusion of technical mastery and artistic vision.

III. From Sacred Altars to Everyday Life: The Evolution of Function

After the mid–Western Zhou period, as the ritual system matured and humanistic thought began to emerge, the style of bronze vessels underwent noticeable transformation. The once fierce and enigmatic taotie motifs gradually diminished, giving way to more rhythmic patterns such as banded designs and ribbon-like qiequ motifs. Vessel forms also became simpler and more utilitarian.

By the Warring States, Qin, and Han periods, bronzes gradually shed their aura of political and religious mystery and entered the realm of daily life. Although the Zeng Hou Yi chime bells remained an important ritual instrument, their precise tuning and wide tonal range reflect a pursuit of music for its own sake. Meanwhile, practical items—bronze mirrors, belt hooks, lamps, and fittings for carriages—proliferated. The exquisitely crafted Changxin Palace Lamp, with its ingenious smoke-absorbing and energy-saving design, still impresses modern viewers with its early “eco-friendly” ingenuity.

Bronze, at last, made its journey from the sacred altar into the everyday world.

Epilogue

Bronze vessels are the childhood imprint of Chinese civilization—material embodiments of ritual and music. They carry within them the early people’s understanding of the world, their reverence for power, and their pursuit of artistic excellence. The tripods, wine vessels, and sets of chime bells not only form essential chapters of Chinese archaeology and art history, but are also deeply etched into the cultural DNA of the nation.

Today, as we encounter these ancient bronzes once more, the green patina that has endured three millennia still gleams with the light of an immortal civilization, telling us the story of its origins and its enduring glory.