Among all gemstones, amber may be the one closest to the essence of time itself.…

Before the Light Fades – Monet

Breath of Dawn: “Impression, Sunrise”

“Impression, Sunrise” is not a realistic depiction of a harbor, but rather an awakening of the senses.

That crimson sun illuminates not the world, but the heart.

Monet no longer cared about the precision of line or the rules of perspective; instead, he cared about how light trembled on water, how mist engulfed the distance, and how colors blended in the air.

He allowed viewers to “feel” the landscape rather than “see” it.

From then on, art ceased to be a mirror that reflected the world, but a window to its perception.

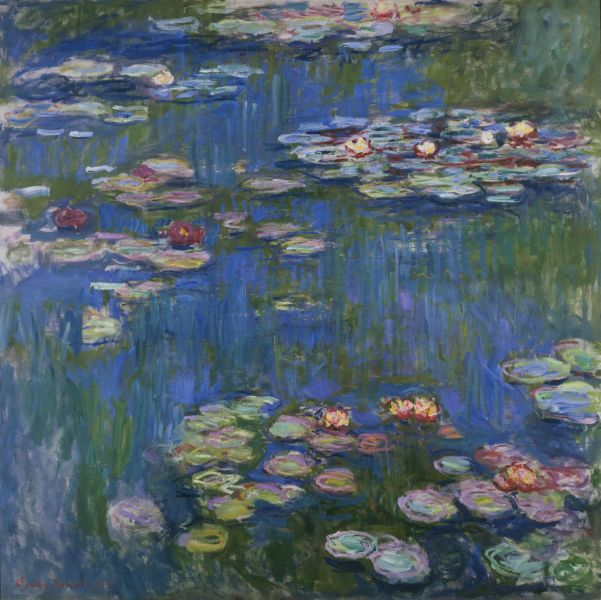

The Lake of Time: The “Water Lilies” Series

In his later years, Monet dedicated the rest of his life to his garden at Giverny.

He planted water lilies, and also planted light.

In that pond, sky, earth, and water intertwined, forming a boundless universe.

Morning light, midday glow, dusk, shadows, a light rain…each reflection was a new world.

He no longer painted “flowers,” but “the flow of light upon them.” Those water lilies are not static plants, but floating passages of time, echoes of life.

In his “Water Lilies,” Monet makes time visible and eternity tender.

A Moment in the Wind: “Woman with a Parasol”

This painting is filled with sunlight, breeze, and love.

The woman in the painting is his wife, Camille, and beside her is their son.

The white dress beneath the parasol is lifted by the wind, and the grass shimmers in layers of green in the sunlight.

Monet did not depict her face—for the “light and shadow” of that moment are the true protagonists.

She is not a frozen image, but a fluid presence, the rhythm of the wind, a breath of time.

In that moment, family, nature, and art merge into one, becoming life’s most tender poem.

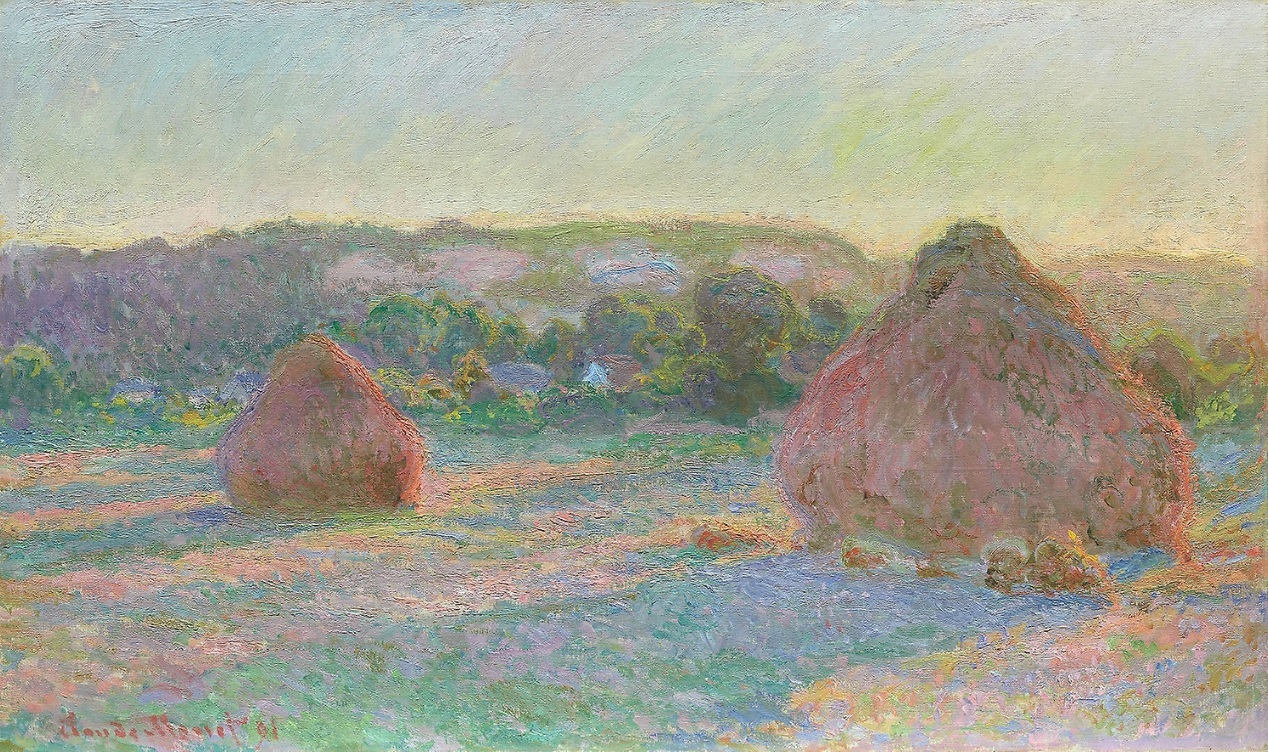

Experiments with Light: The “Haystacks” Series

In the fields, Monet repeatedly confronted the same haystack.

He was not repeating himself, but rather exploring:

Why is the haystack blue-purple in the morning, but golden-red in the evening? He painted countless times—in sunlight, mist, and snow, throughout the changing seasons.

That ordinary pile of grass was imbued with divinity, becoming a “vessel of time.”

He recorded the breath of nature with his eyes and the language of light with his brush.

He made people understand—the world is not a static object, but a flow of light.

Prayer on Stone: The “Rouen Cathedral” Series

In Rouen, Monet faced not nature but the echo of light on stone.

He painted the same cathedral over thirty times.

The silvery blue of dawn, the golden white of noon, the rosy red of dusk…

Each time, he pursued the fleeting play of colors.

He transformed religious architecture into “sculptures of light,”

making the sacred no longer a product of faith, but of time itself.

Before the Light Fades

In his later years, Monet was nearly blind.

But he persisted in painting—for he no longer relied on his eyes to see, but instead memorized the direction of light with his heart. The final brushstrokes of “Water Lilies” are no longer a landscape, but a lasting glimmer of life.

He knew that light would eventually fade, but he also knew that it could be preserved—on the canvas, in the hearts of men.

As we stand in the museum’s exhibition hall today, gazing at that pond of water lilies, that cathedral, that rising sun,

we see not just colors and brushstrokes,

but a lifelong conviction