In the constellation of the Dutch Golden Age, Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn is undoubtedly the…

“Origins of White Jade, Song of Fire and Clay: Tracing a Millennium of Porcelain History”

“When we cradle a smooth blue-and-white porcelain bowl in our hands, or gaze upon a glaze as serene as the sky after rain, have we ever wondered where this millennia-old beauty began?

The story of porcelain is a long epic—each page inscribed with the wisdom of our ancestors, their devotion to beauty, and the rebirth of earth and clay within blazing fire.”

1. Prologue of Antiquity: The Divergence of Pottery and Porcelain

Before porcelain ever made its debut, its predecessor—pottery—had long been an essential part of human life. Yet pottery is porous, absorbent, and dull in sound when tapped. The ancients were not satisfied; they longed for a material that was denser, harder, and more refined.

The key differences lie in two aspects:

Materials:

Pottery is made from ordinary clay, while porcelain requires a remarkable “stone” — kaolin. Rich in aluminum and silica, highly refractory and exceptionally pure, kaolin forms the very “bones” of porcelain.

Temperature and Glaze:

Pottery is typically fired at temperatures below 800°C, whereas porcelain requires extreme heat—above 1200°C—so that the body vitrifies completely, becoming dense and non-porous. At the same time, the glaze on its surface melts into a thin, glassy layer, giving porcelain its luminous and silky finish.

Thus, the great evolution from pottery to porcelain quietly began on the vast land of China.

2. Budding in the Shang and Zhou: The Birth of Early Celadon

Around the 16th century BCE, during the Shang dynasty, craftsmen in regions such as today’s Jiangxi and Zhejiang made an accidental discovery while firing impressed hard pottery. Some vessels emerged with a thin, pale greenish-yellow glaze on their surface. Their bodies were finer, and when struck, they produced a clear, metallic ring.

These were the first “proto-celadon” wares.

Although their glaze was uneven and their bodies grayish-white—still rough compared with the refined porcelains of later centuries—they already possessed the essential qualities of true porcelain. They were the newborn “quasi-porcelain” created from the union of fire and clay, opening the prologue to porcelain’s three-thousand-year history.

3. Maturity in the Eastern Han: The Establishment of True Porcelain

By the late Eastern Han (2nd century CE), porcelain-making technology experienced a revolutionary leap in the middle reaches of the Cao’e River in Shangyu, Zhejiang. Craftsmen there improved the structure of the dragon kiln, enabling it to reliably reach temperatures of 1300°C. They selected and refined local kaolin to create a dense, sturdy body; at the same time, they successfully formulated a lime glaze made from plant ash.

When these three elements came together in perfect harmony, the first true porcelains in Chinese—and indeed world—history were born: celadon.

These wares were well vitrified, with extremely low water absorption. Their bodies were fully glazed, the surface clear and lustrous, glowing with a soft green hue like a mountain spring. This breakthrough marked porcelain’s complete separation from the broader family of pottery—standing as a distinct and extraordinary material in its own right.

4. Accumulation in the Wei, Jin, and Northern–Southern Dynasties:

Southern Green and Northern White

During the Three Kingdoms, Jin, and Northern–Southern Dynasties, the porcelain industry flourished, giving rise to distinct regional styles.

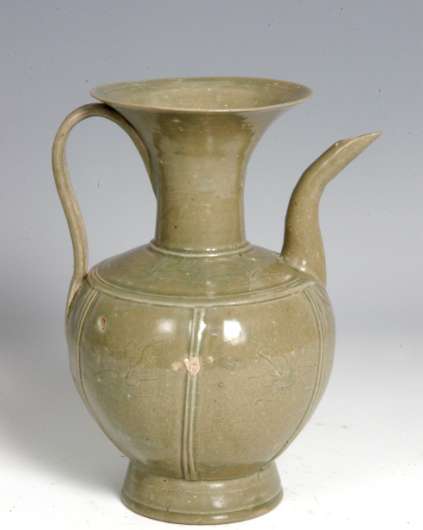

In the south, represented by the Yue kilns of Zhejiang, celadon reached extraordinary heights. Complex forms such as chicken-head ewers and lotus-shaped zun vessels appeared, adorned with refined decoration. Their green glazes, clear and vibrant, were celebrated as “a thousand peaks in emerald.”

In the north, artisans began experimenting with white porcelain. Its difficulty lay in removing iron from the clay and glaze to achieve true whiteness. Though northern white wares of this period often showed slight greenish or yellowish tones, the emerging pattern of “southern celadon and northern white” had already taken shape.

5. Splendor of the Tang and Song Dynasties:

The Pinnacle of Porcelain Art

In the Tang dynasty, porcelain—like Tang poetry—entered a magnificent golden age. The pattern of southern green and northern white became firmly established:

Yue celadon, as smooth as ice and as soft as jade, earned high praise from Lu Yu, who likened it to “jade and ice,” and from poets who wrote, “When the autumn wind and dew open the kilns of Yue, they summon forth the emerald hues of a thousand peaks.”

Xing kiln white porcelain, pure as silver and snow, was admired for its clean, unadorned beauty and was widely traded across China and beyond.

The Song dynasty, however, marked the philosophical zenith of Chinese porcelain. Its pursuit lay not in ornate decoration, but in the purity of glaze, the elegance of form, and the depth of poetic mood. The Five Great Kilns—Ru, Guan, Ge, Jun, and Ding—pushed the aesthetics of naturalness, restraint, and quiet beauty to their utmost.

Ru ware’s “sky-blue after rain, where clouds break open” embodies a uniquely delicate and unrepeatable blue.

Ge ware’s “golden threads and iron lines” reveal a beauty born from the cracks and imperfections of its patterned glaze.

Jun ware’s “one color enters the kiln, ten thousand colors emerge” captures the unpredictable magic of fire in its ever-changing hues.

6. Inheritance and Innovation in the Yuan, Ming, and Qing:

Porcelain Goes Global

In the Yuan dynasty, the rise of blue-and-white porcelain opened a new era in ceramic decoration. Cobalt pigment was painted onto a white body, then covered with a clear glaze and fired once at high temperature, producing crisp, vivid blue patterns that quickly captivated the world.

During the Ming and Qing dynasties, Jingdezhen became the globally renowned “Porcelain Capital.” Techniques such as underglaze red, wucai (five-color), doucai (contrasting colors), famille verte, famille rose, and falangcai enamel emerged one after another, transforming porcelain into a vessel for ultimate luxury and superb craftsmanship. Through the Maritime Silk Road, Chinese porcelain—one of the most prized commodities and a cultural ambassador—spread across Eurasia, profoundly shaping lifestyles and artistic tastes around the world.

The English word “china” refers both to China and to porcelain—itself a silent testimony to centuries of global exchange.

Epilogue: The Rebirth of Earth and Fire

From the accidental glimmer of glaze in the Shang and Zhou, to the epoch-making maturity of the Eastern Han; from the philosophical simplicity of the Tang and Song, to the dazzling splendor of the Ming and Qing—

the origin of porcelain is a three-thousand-year journey of experiment and creation. Born from daily life yet elevated to art, created in China yet belonging to the world.

Every piece of porcelain preserves the dreams of a handful of clay and the memory of a single flame. It is not only a vessel for holding things, but a vessel of civilization itself—bearing the soul of Eastern aesthetics and whispering to us even today the timeless legend of earth and fire.