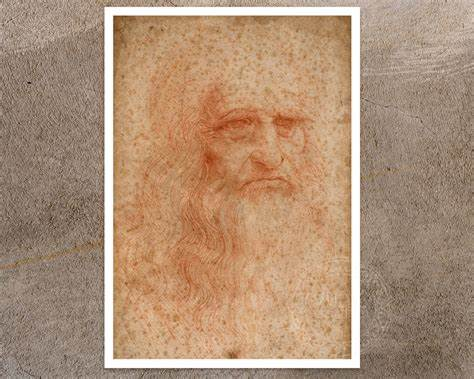

A Transcendent Image by Leonardo da Vinci In the history of Western art, few images…

Frozen Light in Porcelain: The French Elegance of Sèvres

In the history of French art, there exists a kind of white—purer than snow, softer than clouds; and a kind of blue—deep as dusk, yet noble as a crown. It does not belong to nature, but is born from the union of flame and artistry. Its name is Sèvres.

I. A Royal Beginning: From Dream to Monarchy

18th-century France was the golden age of Rococo art.

The Hall of Mirrors in Versailles reflected the brilliance of power, and Louis XV together with Madame de Pompadour defined the era’s ultimate notion of “elegance.” In this cultural atmosphere, the Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory came into being.

In 1756, the manufactory officially moved to the small town of Sèvres near Paris, becoming the royal porcelain workshop of the French monarchy. It was not merely a factory, but a laboratory of art. The king personally invested in it, and Madame de Pompadour guided its artistic direction. The finest artisans and painters gathered there.

The mission of Sèvres was not only to make tableware, but to use porcelain as a medium to express the pinnacle of French taste and spirit.

From then on, Sèvres became a symbol of royal authority and refined aesthetics. Its works were displayed in Versailles, the Louvre, and Fontainebleau, and given as diplomatic gifts to monarchs and nobles around the world. Each piece of Sèvres porcelain was like a letter from France — conveying elegance and an idealistic devotion to beauty.

II. The Art of Fire and Powder: Craft at Its Peak

The glory of Sèvres does not rest solely on its history but on its craftsmanship.

Sèvres was first renowned for its soft-paste porcelain (pâte tendre) — a delicate, luminous, yet notoriously difficult material. Its fragility made firing extremely risky, but the result was a porcelain with an unmistakable gentle glow and warmth. After countless experiments, the manufactory later succeeded in creating hard-paste porcelain (pâte dure) comparable to that of Jingdezhen, raising Sèvres craft to a new height.

One of its most famous colors is the incomparable Sèvres blue (bleu de Sèvres) — a rich azure, as deep as the French twilight and as noble as a royal mantle. Paired with powdered gold, hand-painted flowers, and classical motifs, each piece becomes a poem, a symphony of light and shadow.

The process itself resembles a ritual: shaping, drying, bisque firing, glazing, painting, gilding — all done by hand, every stroke infused with the soul of the artist. As Sèvres craftsmen often say:

“We do not make porcelain — we sculpt time.”

III. The Aesthetic of Sèvres: From Rococo to the Modern Age

The charm of Sèvres lies in its role as both guardian of tradition and explorer of the future.

During the Rococo period, it captured the romance of aristocratic salons with airy curves and lavish floral motifs. In the Neoclassical era, it reflected the Enlightenment’s rational spirit with balanced compositions and harmonious symmetry. With each era, Sèvres used porcelain as a canvas to portray the shifting aesthetic of French society.

In the 20th century, innovation became a part of its heritage. Modern artists such as Picasso, Chagall, and Arman collaborated with Sèvres, infusing modern artistic language into ancient techniques. Sèvres never resisted change; instead, it sought new life within the textures of tradition. As Roland Barthes wrote:

“Elegance is not the rigidity of form, but the continuity of time.”

Today, the Sèvres manufactory still stands at the edge of Paris and remains under the direct administration of the French Ministry of Culture. It is not merely a production site but a living temple of art. Craftsmen continue the 18th-century techniques, while contemporary artists explore new forms. Each year, Sèvres releases limited-edition works that reinterpret classical style through modern design, allowing royal artistry to shine anew.

IV. A Symbol of the French Spirit: Dignity and Warmth in Porcelain

Sèvres porcelain is not merely beauty in material form — it is a cultural symbol.

It represents three essential qualities of the French spirit:

rationality, romance, and refinement.

Rationality appears in the strict standards of craftsmanship and the order of its forms.

Romance flows through its colors and delicate decorations.

Refinement permeates every line of gilding and every layer of glaze.

The beauty of Sèvres is a silent power. It does not shout, yet it defines nobility without words. Found on state banquet tables or displayed behind museum glass, a Sèvres piece always stands like an elegant French aristocrat, quietly telling the story of artistic dignity.

Thus, Sèvres is not merely decoration — it is a way of life: transforming the everyday into art, turning time into elegance.

V. Light That Never Fades: From Royalty to the World

For more than two centuries, the name Sèvres has transcended borders. From Paris to London, Saint Petersburg to Tokyo, its works are collected, admired, and revered.

Each piece of Sèvres porcelain tells a story of craftsmanship, heritage, and faith in beauty.

In an age dominated by speed and mechanical replication, Sèvres feels especially precious. It reminds us that true luxury lies not in quantity or price, but in the depth of time and the warmth of the hand.

That blue, that gold, that shadow beneath the glaze — all are the craftsman’s pursuit of eternity.

As flame rises within the kiln and the porcelain transforms in its fiery rebirth, the story of Sèvres continues.

It journeys from palaces to the world, from history to the future, becoming an everlasting star in French culture.

Epilogue: The Light on Porcelain Is the Heart of France

Sèvres porcelain is more than an art history chapter — it is a symbol of spirit.

It teaches us that beauty can be shaped by hand, and time can be captured by art.

The light sealed within its porcelain does not merely illuminate 18th-century Versailles — it gently illuminates our lives today.

In the depths of Sèvres blue, we see not only the sheen of porcelain, but the elegant soul of France, unchanged through centuries.