Have you ever wondered what change occurred in the world when the first sculpture was…

Between form and formlessness

Painting is not merely a depiction of the world’s forms; it is more of a question about “how perception occurs.” Between the visible form and the invisible formless, art unfolds its deepest dimension.

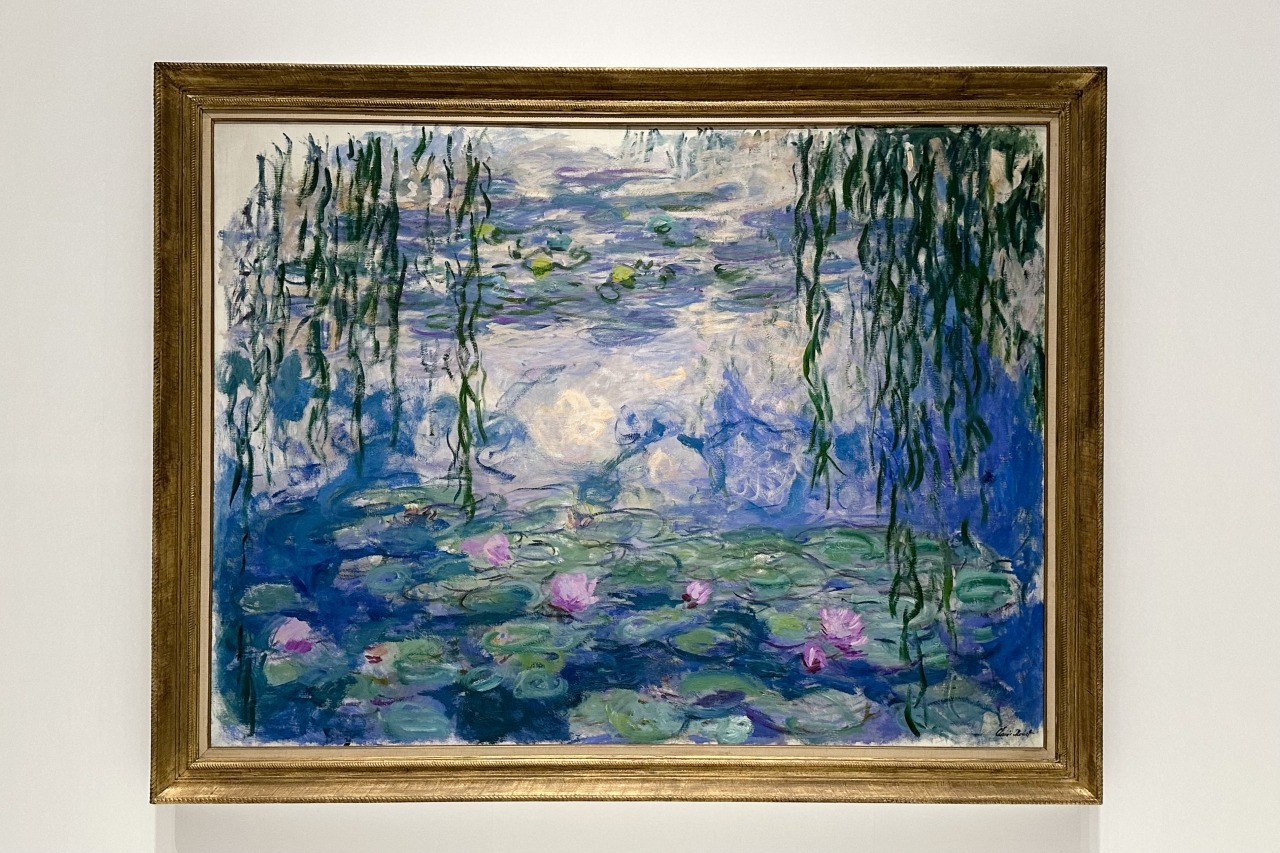

Claude Monet’s “Water Lilies” series is a classic example of this repeated testing of boundaries. The water, flowers, and reflections are constantly decomposed and reassembled in the painting, their outlines fading away, and the objects seem to breathe in light and color. The water lilies remain, but are no longer objects to be gazed upon; instead, they become the intersection of time, light, and emotion. Monet no longer depicts the “form of the water lilies,” but rather the act of seeing itself—how, in that instant, the world enters the eye and dissolves into consciousness.

In “Water Lilies,” form is diminished, while time is extended. The scene is neither dawn nor dusk, but rather an overlap of multiple moments. It is precisely within this ambiguity that the intangible—the changes in light, the humidity of the air, and the viewer’s emotions—quietly emerge.

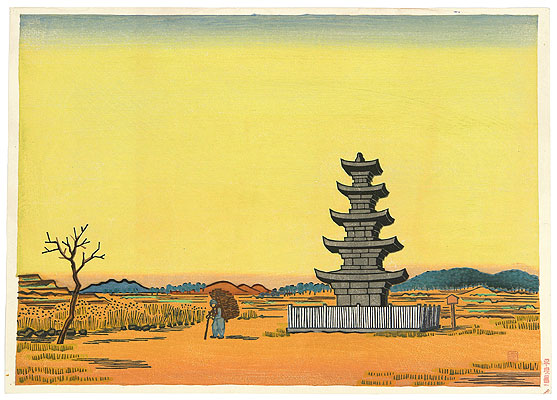

If we shift our focus from the colors of Impressionism to the world of Eastern printmaking, Japanese woodblock printmaker Unichi Hiratsuka responds to the theme of “form and intangibility” in a completely different yet equally profound way. As an important representative of the “Creative Printmaking Movement,” Hiratsuka adheres to the creative principle of “self-painting, self-carving, and self-printing,” making his works the result of the interaction of the artist’s body, time, and materials.

In his works, such as woodblock prints depicting temples, ancient pagodas, and tranquil landscapes, architecture is often simplified into solid and restrained forms, with steady lines and concise compositions. However, what truly dominates the picture is not the architecture itself, but the “emptiness” around it—vast blank spaces, still skies, and silent spaces. These undepicted parts give the picture a power that transcends form.

Taking Unichi Hiratsuka’s temple-themed works as an example, the natural texture of the wood grain and the rhythm of the carving are completely preserved. The resistance of the wood, the pauses of the knife, and the hesitation of the hand are all transformed into traces in the picture. The form is therefore no longer a smooth, perfect reproduction, but a state of “being formed”. The invisible time, the traces of labor, and the focus of the spirit are revealed through the materiality of the woodblock.

If Monet dissolved form into light in “Water Lilies,” then Unichi Hiratsuka solidified form through restraint, allowing the intangible spirit and time to sink into the depths of the painting. One is a fluid observation, the other a serene gaze; one dissolves boundaries with color, the other establishes existence with knife marks.

However, both approaches essentially share the same path: they both refuse to confine art to the mere “reproduction of objects,” instead transforming the work into a field of perception. The viewer is not a bystander, but invited into the picture, to co-create an understanding of the intangible with the painter.

Between the form and the intangible, art is no longer an answer, but a continuously unfolding experience. When we gaze upon Monet’s water lilies, or the silent architecture carved by Hiratsuka Un, what we see may well be the echo of our own perceptions left behind in time.