Have you ever wondered what change occurred in the world when the first sculpture was…

From Urbino Boy to Renaissance Master: Raphael’s Path to Fame in Painting

In the brilliant constellation of the Renaissance, Raphael Sanzie, with his short life of 37 years, wrote a legendary chapter in art history. As the youngest of the “Three Masters of the Renaissance,” he lacked Leonardo da Vinci’s long explorations and Michelangelo’s long creative life, yet he conquered his era with his unique, gentle, and elegant style. From a young apprentice at the Urbino court to surpassing two giants to become the chief painter of the Vatican, his path to fame was a perfect fusion of talent, diligence, and opportune timing, and a testament to the ultimate blossoming of humanism in art.

Early Learning and Mastery: The Artistic Budding of Urbino

Raphael was born in 1483 in Urbino, Italy, into an artistic family. His father, Giovanni Sansi, was the court painter to the local duke. In his father’s studio, Raphael displayed extraordinary artistic talent from a young age, spending his childhood surrounded by paper, brushes, and paints. His father not only taught him painting techniques but also familiarized him with court etiquette and the social atmosphere, an experience that laid the groundwork for his future commissions from powerful figures.

When his father realized he couldn’t satisfy his son’s thirst for knowledge, he sent the 14-year-old Raphael to Perugia to study under the Umbrian master Perugino. Raphael’s comprehension was remarkable; he quickly and accurately grasped his teacher’s serene and graceful style, and his works were often mistaken for his teacher’s own. At the age of 16, he received his first formal commission—to paint “The Banner of the Holy Trinity”—marking his first step into the world of professional painting. In 1504, at the age of 21, Raphael experienced a pivotal turning point. In a fierce competition, he defeated his teacher’s studio to win a lucrative painting commission, officially declaring his transcendence of his mentor. That year, upon hearing that Leonardo da Vinci was working on “The Battle of Anghiari” and Michelangelo had just completed “David” and was working on “The Bathers,” he resolutely put aside his work and embarked on a “pilgrimage” to Florence.

Refinement and Transformation: A Fusion of Florentine Styles

Upon arriving in Florence, Raphael was captivated by the artistic atmosphere of this humanist center. He not only timidly knocked on Michelangelo’s door, spending entire days before the draft of *The Bathers*, but also immersed himself in studying the techniques of various masters, absorbing scientific theories such as perspective and anatomy, and integrating the compositional essence of Leonardo da Vinci with Michelangelo’s expressive power of the human form into his own creations. Here, he was no longer simply imitating, but began to explore his own style, especially infusing religious themes with human warmth, breaking the coldness of medieval religious paintings.

Between 1504 and 1508, Raphael’s style fully matured, giving rise to a series of classic Madonna paintings, including *Madonna of the Meadow*, *Madonna with the Goldfinch*, and *Madonna of the Garden*, all representative works of this period. His Madonna was no longer a lofty goddess, but a mother radiating earthly happiness, her posture of turning to watch over playful children, the soft lines, and the poetic atmosphere perfectly embodying the core idea of ”humanity as the center.” These works brought Raphael fame in Florence and laid a solid foundation for his later pursuit of artistic excellence.

Peak and Glory: The Papal Glory of Rome

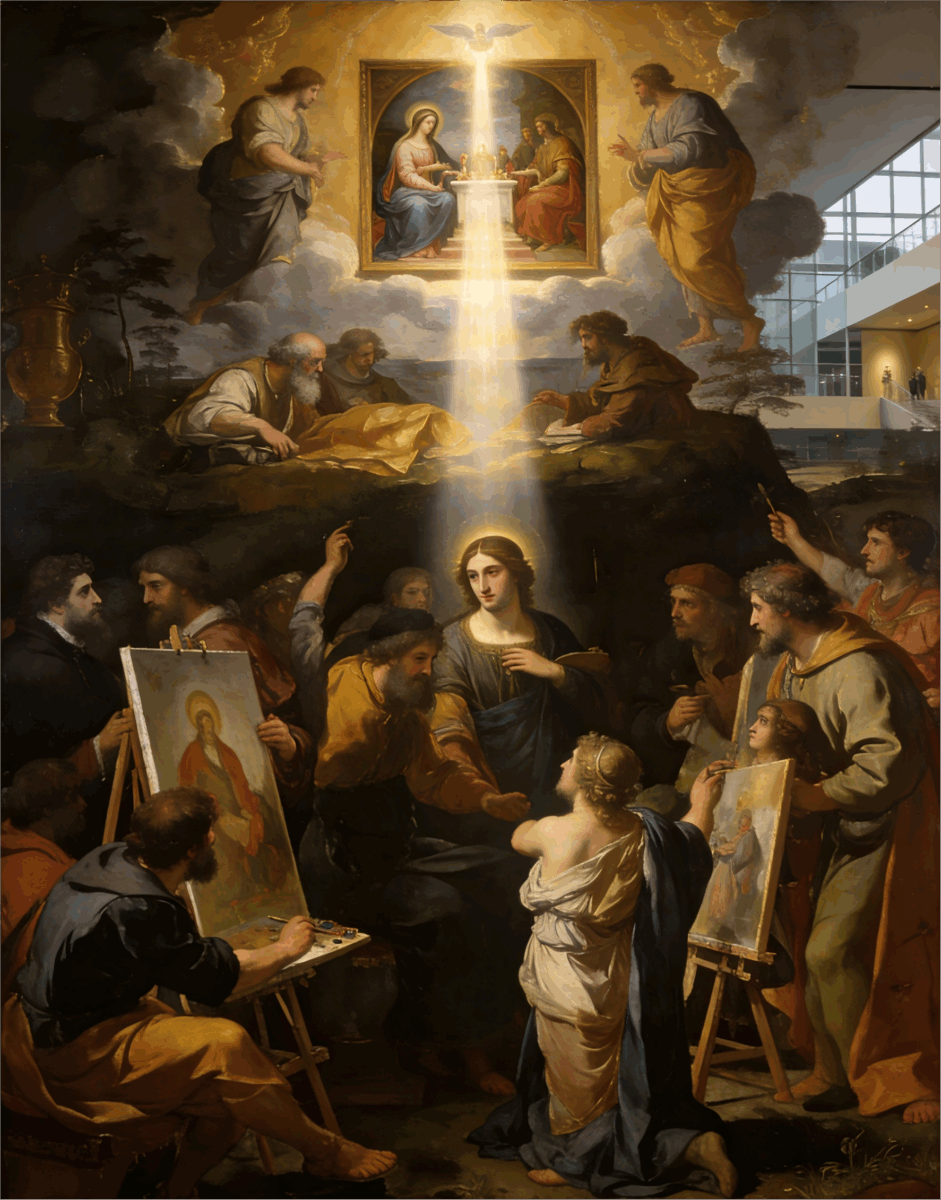

In 1508, through the introduction of the architect Bramante, Raphael received the most important opportunity of his life—defeating Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo in a fierce competition to be invited to Rome to decorate the Vatican Palace for Pope Julius II. This appointment became a milestone in his career, and the frescoes in the “Signature Room” that he was responsible for painting propelled his artistic achievements to their zenith. Among them, *The School of Athens* is a classic, featuring Plato, Aristotle, and other philosophers from ancient and modern times gathered together against a backdrop of a magnificent vaulted dome. The composition, with its constellation surrounding the moon, creates a vibrant atmosphere of free debate, its grandeur and varied expressions signifying a revival of rational spirit. *The Sacramental Dispute* skillfully blends religious themes with realistic aesthetics, demonstrating an exceptional mastery of complex scenes.

Based on his exceptional work, Raphael was granted the title of “Chief Painter” by the Church in 1509 and served two popes. He not only completed masterpieces such as the *Sistine Madonna* and *The Triumph of Galatasaray*—the *Sistine Madonna* being considered the pinnacle of Madonna paintings due to its perfect pyramidal composition and serene atmosphere—but also took on the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica and served as the Superintendent of Antiquities in Rome. At the peak of his career, he also painted a portrait of his friend, the humanist scholar Castiglione, using pure chiaroscuro to express the character’s inner yearning and the diplomat’s calm and cautious demeanor, demonstrating his cross-disciplinary artistic achievements and becoming one of the most sought-after artists in Europe.

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Transience and Eternity: The Legacy of Artistic Spirit

In 1520, Raphael died suddenly from an acute illness at the young age of 37. Though his life was short, he left behind over three hundred works. His elegant, harmonious, and bright artistic style became a model of Classical art. The phrase “like Raphael’s Madonna” remains a common Italian expression of praise for female beauty. From a young apprentice in Urbino to a Renaissance master, Raphael exemplified the power of art through his talent and diligence. His path to fame is not only a personal story but also encapsulates the era’s transformation from theocracy to humanistic awakening during the Renaissance. His artistic spirit transcends five centuries and continues to nourish countless creators today.