Before the mysterious smile of the Mona Lisa in the Louvre, and beneath the profound…

The Origin of the Chime Bells: A Millennium of Coexistence Between Bronze and Music

Prologue: Hearing the Echoes from the Depths of Time

When the very first bronze bell was cast in a workshop of the Western Zhou, no one could have foreseen that this ritual vessel—created for solemn ceremonies—would, centuries later, evolve into a cosmos of tones as precise and ordered as the stars.

The bianzhong was not the sudden invention of a sage-king, but the result of a millennia-long coevolution of technology and musical thought.

Chapter I: Distant Origins — From Pottery Bells to Bronze Bells

Prelude: Echoes of the Neolithic Age

Around 6,000 years ago, pottery bells had already appeared in northern China (such as those unearthed at the Taosi site in Xiangfen, Shaanxi). These hollow clay bells contained small pellets that produced sound when shaken, likely used in rituals or for signal transmission.

By the Xia and Shang periods, bronze-casting technology had matured, and bronze bells began to emerge. They were often hung on chariots, animals, or the garments of nobility. At this stage, bells were simply individual sound-making devices; no musical system or tonal structure had yet taken shape.

Chapter II: Emergence — The “Sound of Metal and Stone” in Western Zhou Ritual Music

The Beginning of an Ordered World: “The ringing of bells and the dining of cauldrons”

After the founding of the Western Zhou dynasty, the Duke of Zhou formalized rituals and music, integrating musical instruments into the social hierarchy. The “Musical Suspension System” was established, prescribing the number and arrangement of bells and chimes permitted for kings, lords, and officials.

Archaeology’s First Clear Evidence

In the early Western Zhou tomb at Zhuyuangou, Baoji, Shaanxi (c. 11th century BCE), archaeologists unearthed a set of three yongzhong bells — the earliest known prototype of the bianzhong.

Characteristics of this period: small in number (usually sets of three), narrow in range, and used mainly to sound simple foundational tones in rituals or to mark ceremonial rhythm.

Key breakthrough: people began intentionally combining bells of different sizes to explore pitch relationships.

Chapter III: Breakthrough — The Spring and Autumn Era’s “Two Tones from One Bell” Revolution

An Accidental Discovery that Changed History

During the Spring and Autumn period, bronze artisans likely discovered—perhaps while tuning a bell—that striking the center of the bell’s face (the frontal node) and striking the side (the lateral node) produced two distinct pitches.

This physical property was soon consciously harnessed and standardized.

Evidence of Technological Mastery

In the Xiaosi Chu tomb in Xichuan, Henan (late Spring and Autumn period), the bianzhong of Prince Haoshi was unearthed. These bells were deliberately cast with two striking zones, and inscriptions clearly indicated their pitch names.

Significance

The “one bell, two tones” innovation made it possible for fewer bells to carry a wider musical scale, marking the transition of bianzhong from a primarily rhythmic instrument to a true melodic one.

Chapter IV: Zenith — The Cosmic Achievement of Warring States Bianzhong

Marquis Yi of Zeng: An Underground Concert Hall

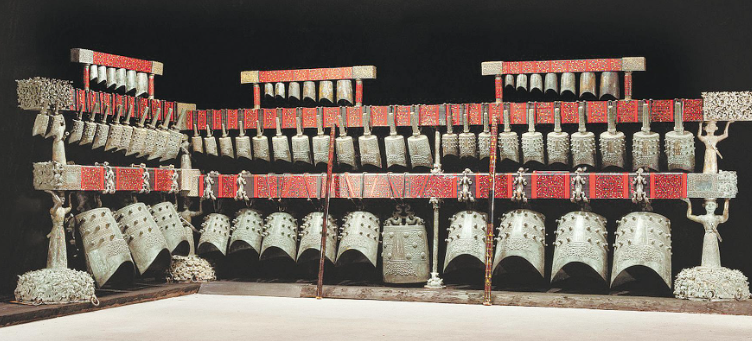

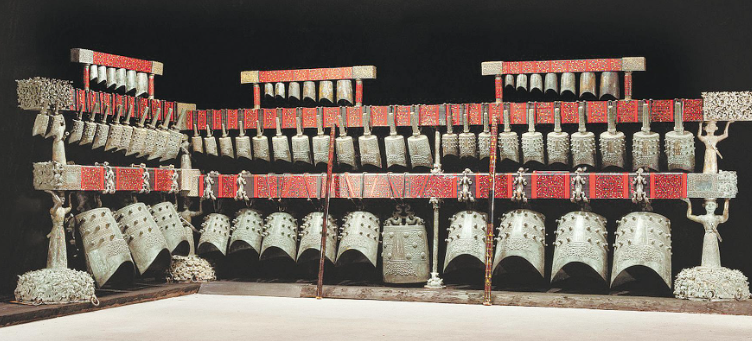

In 433 BCE, when Marquis Yi of Zeng was laid to rest, he descended into the earth accompanied by the most magnificent bronze musical system ever discovered:

-

65 bells, arranged in three tiers and eight groups, with a total weight of five tons.

-

A pitch range spanning five and a half octaves, with a complete chromatic set of twelve semitones in the central register.

-

Each bell bears inscriptions naming its pitches, comparing tonal systems used by states such as Chu, Qi, and Jin — effectively a musical encyclopedia of the pre-Qin world.

Why Did the Art Reach Its Peak in the Warring States Period?

Technological Maturity:

The perfection of the lost-wax casting method allowed artisans to control bell thickness and shape with remarkable precision.

Ritual Collapse and Cultural Competition:

As feudal order disintegrated and states vied for dominance, each sought to demonstrate cultural might. Casting grand bell sets became a potent symbol of national power.

Intellectual Crosscurrents:

Among the Hundred Schools of Thought, Confucians argued that “music and governance are one,” while Daoists contemplated the idea of “the greatest sound is scarcely heard.” Music acquired new philosophical depth.

Chapter V: Decline — The “Last Resonance” After Qin and Han

The End of the Bronze Age

With the unification under the Qin and Han dynasties, the bianzhong transitioned from the “music of competing states” to a ceremonial ornament of imperial court rituals, diminishing its practical musical function.

A Cultural Shift

The Silk Road introduced new instruments—such as the pipa and konghou—bringing lighter, more lyrical musical styles. The massive and solemn bianzhong gradually faded from the mainstream.

Loss of Craftsmanship

After the Eastern Han, the “two tones from one bell” technique became an esoteric craft and was eventually lost. Although later courts attempted to recreate bell sets, they served largely as ceremonial décor, and their pitch accuracy could no longer match the achievements of antiquity.

Chapter VI: Reunion — The Awakening of Modern Archaeology

The Strike That Changed 1978

After the discovery of the Marquis Yi of Zeng bianzhong in 1978, musicians performed The East Is Red on the ancient bells, broadcasting the sound to the world via satellite.

The silence of 2,400 years was broken — and people were astonished to find that:

Its tuning aligns almost perfectly with today’s C major scale.

The inscriptions revealed a musical system that established a twelve-pitch framework over a millennium before Europe.

Epilogue: What Is the “Origin” of the Bianzhong?

The birth of the bianzhong was never merely a story of technological progress:

It is the material form of ritual — the Western Zhou aspiration for order embodied in the phrase, “to feast beside cauldrons and drink to the sound of bells.”

It is the metaphysics of sound — the ancient belief in yin and yang cast into the very structure of “one bell, two tones” (the frontal strike as yang, the lateral strike as yin).

It is the dialogue of civilizations — the coexistence of Chu, Zhou, and Jin pitch names inscribed on the bells, imagining a shared musical cosmos in an age of division.

Ultimately, what we hear is not merely the vibration of bronze.

It is a civilization of rites and music attempting to use the most enduring metal to preserve the most fleeting time;

to use the most precise pitch to harmonize the most turbulent world.

Every set of bianzhong is an audible monument to order and harmony.

Today, as we stand in museums and gaze upon these monumental arrays of bronze, perhaps we should listen more closely:

within the depths of each bell still echoes the ancient artisans’ question to heaven and earth—

“How can metal be taught to sing? How can a moment be made eternal?”

The origin of the bianzhong is, in truth, the millennia-long answer to that very question.