The wisdom of Shakyamuni Buddha is not an abstract theoretical system, but a practical philosophy…

The Allure of Chinese Painting: Solace for the Soul, Resonance with Nature

Chinese painting, an ancient and captivating art form, carries humanity’s pursuit of beauty and contemplation of life. From classical landscapes and bird-and-flower paintings to modern abstract art and expressionism, it communicates the artist’s innermost emotions and inspirations through a unique visual language.

History and Origins

Traditional Chinese art, especially ink-wash painting (shuǐmò), merges art with philosophy and poetry, creating a distinct cultural expression. The sublime heights of landscape painting and the delicate vitality of bird-and-flower subjects arise from a profound understanding of nature. Through variations in brushwork and ink tones, artists convey reverence and love for nature and life.

As a profound and expressive art form, painting remains indispensable to human culture. It transmits emotion and thought, offering tranquility and beauty in a complex world. Whether appreciating a masterpiece or immersing oneself in creation, it elevates the spirit.

Song Dynasty: The Soul of Investigating Things to Attain Knowledge (Géwù zhìzhī)

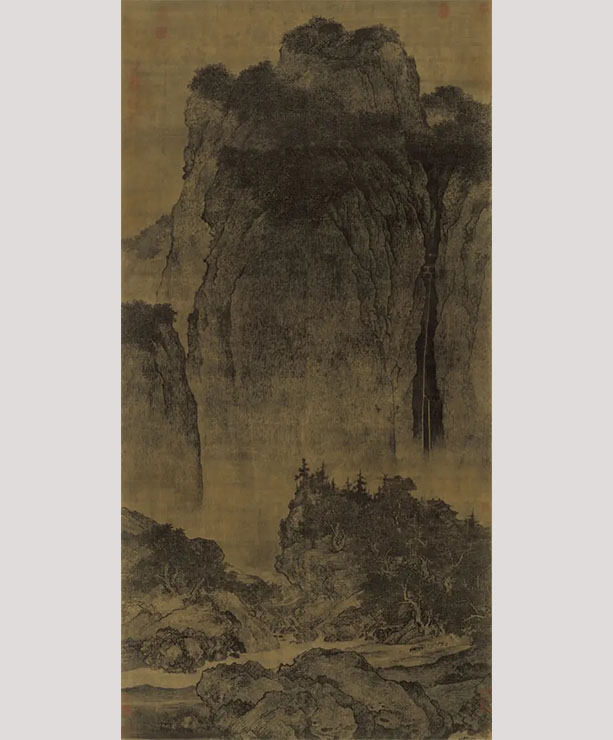

Fan Kuan, Travelers Among Mountains and Streams (Xīshān Xínglǚ Tú)

Technical Breakthrough: Raindrop texture strokes (yuándiǎn cūn) sculpt granite-like mountains; a monumental composition (peak occupying two-thirds of the canvas) embodies the cosmos of “Heaven, Earth, and Humanity.”

Metaphorical Detail: A diminutive merchant caravan in the lower right contrasts nature’s majesty, visualizing the Song ethos of géwù zhìzhī.

Legacy: Hailed by Western scholars as the “Oriental Mona Lisa.”

Zhang Zeduan, Along the River During the Qingming Festival (Qīngmíng Shànghé Tú)

Epic Handscroll: 5.28m silk scroll depicting 814 figures, 28 boats, and 60+ livestock, panoramically documenting Bianjing’s canal transport, markets, and city defenses.

Hidden Social Critique: Conflicts on Rainbow Bridge, idle guards, and empty tax granaries subtly expose late Northern Song societal crises.

Ming Dynasty: Revolution of Ink and Brush

Shen Zhou, Lofty Mount Lu (Lúshān Gāo Tú)

Literati Painting Monument: 194×98cm monumental paper scroll honoring his teacher Chen Kuan’s 70th birthday, using Mount Lu as a metaphor for scholarly virtue.

Technical Heritage: Interwoven “ox-hair” (niúmáo) and “unraveled-rope” (jiěsuǒ) texture strokes’s dense style, with misty voids embodying ethereal emptiness.

Historical Significance: Wu School’s first large-scale landscape, pioneering literati art commercialization.

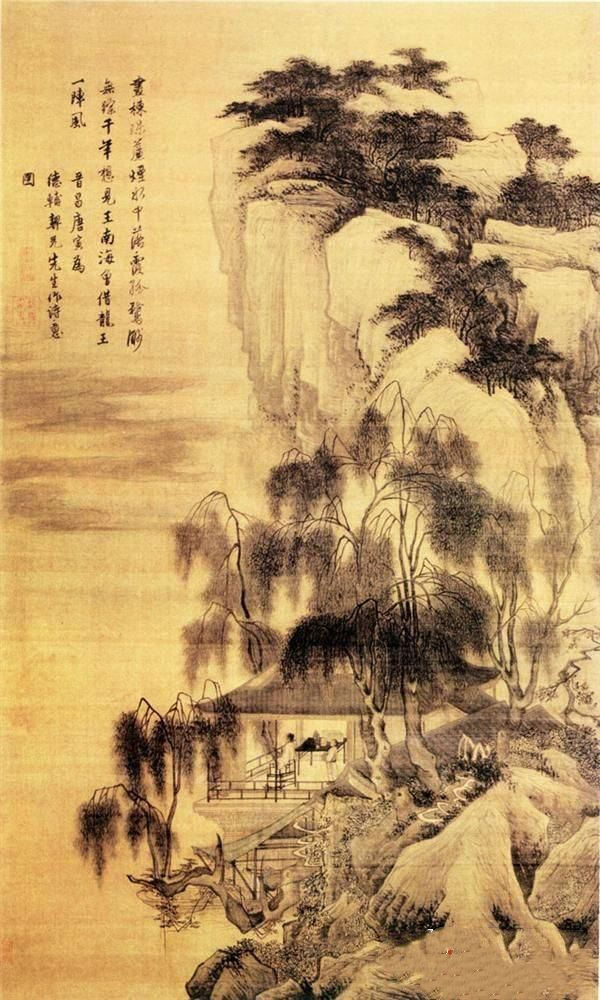

Tang Yin, Lone Goose over Autumn Waters (Luòxiá Gūwù Tú)

Poetry of Disillusionment: Inscribed verse “Painted towers and pearl curtains fade in misty waters / Where sunset clouds and lone wild geese vanish from sight” alludes to Wang Bo’s literary genius, mirroring Tang’s unfulfilled ambitions.

Ink Experimentation: “Axe-cut” (fǔpǐ) strokes define rocks; pale ochre washes suggest dusk; willow branches rendered with calligraphic “flying-white” (fēibái) technique.

Qing Dynasty: East-West Convergence

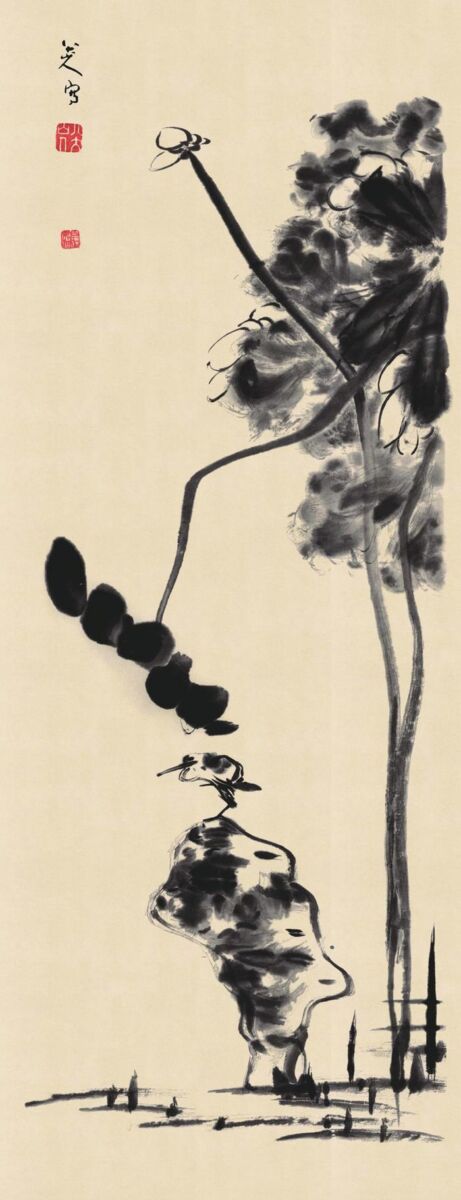

Bada Shanren (Zhu Da), Lotus and Waterbird (Héhuā Shuǐniǎo Tú)

Symbolic Vocabulary: Side-eyeing bird, inverted perilous rock, and withered lotus construct a “laughing through tears” world of Ming loyalist trauma.

Ink Mastery: Parched brush and scorched ink for lotus stems; tear-like dense moss dots; sparse composition defying classical aesthetics.

Giuseppe Castiglione (Láng Shìníng), One Hundred Horses (Bǎi Jùn Tú)

Technical Fusion: European chiaroscuro models equine muscles; Chinese silk pigments render fur luminosity; traditional multi-perspective organizes the scroll.

Cultural Negotiation: Shadows omitted for Qianlong’s tast

Modern Era: Fission of Tradition

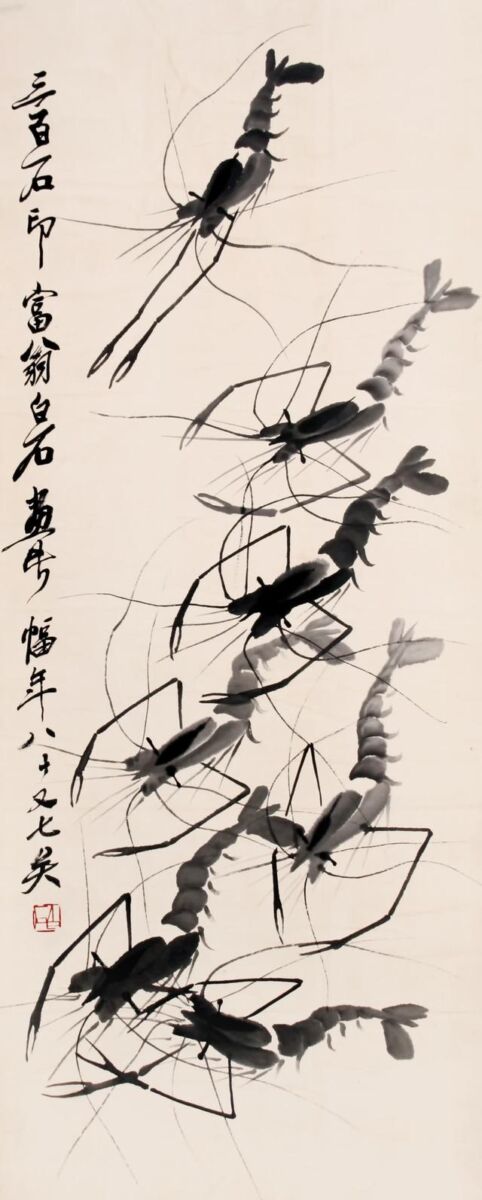

Qí Báishí, Shrimp

Ink Miracle: Pale ink dots create translucent bodies; vertical dark ink strokes form eyes; moist side-brush sweeps render antennae—shrimp seem to swim across the paper without painted water.

Aesthetic Manifesto: “The essence of painting lies between resemblance and non-resemblance. Too close to reality is kitsch; too far from it is deception.”

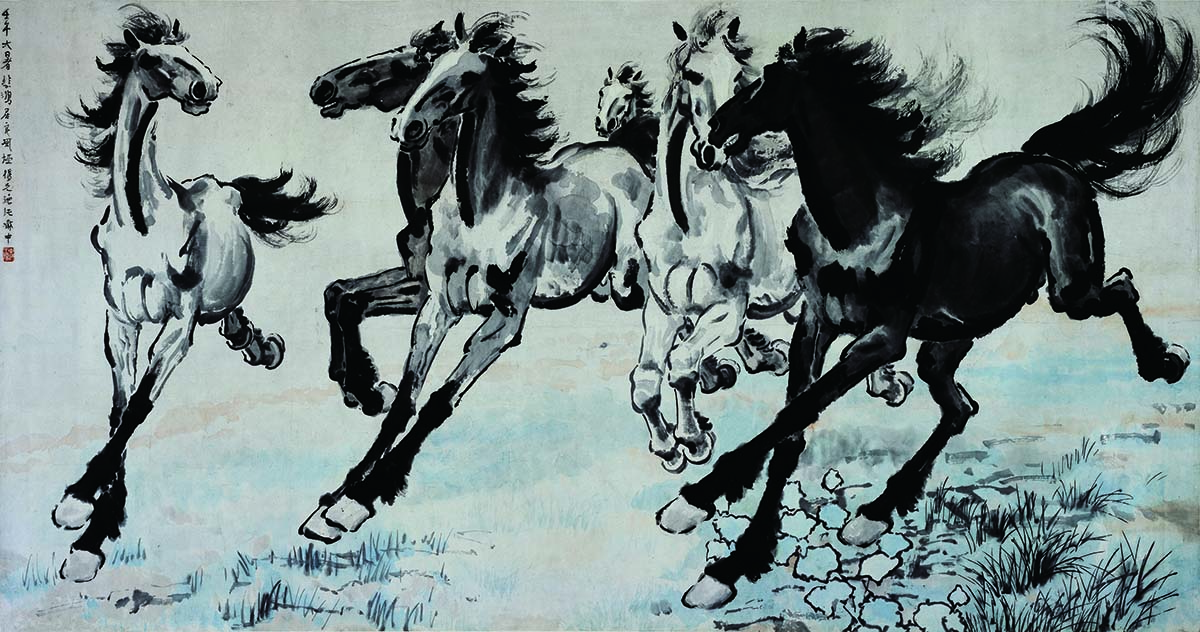

Xú Bēihóng, Galloping Horse

East-West Synthesis: Anatomically precise neck curve; mane rendered with cursive-script vigor; negative background conveys thunderous motion.

Symbol of an Era: Painted in Malaysia (1941), inscribed “heart burning with anxiety”, embodying anti-Japanese resistance spirit.

Collection: Xu Beihong Memorial Museum, Beijing.

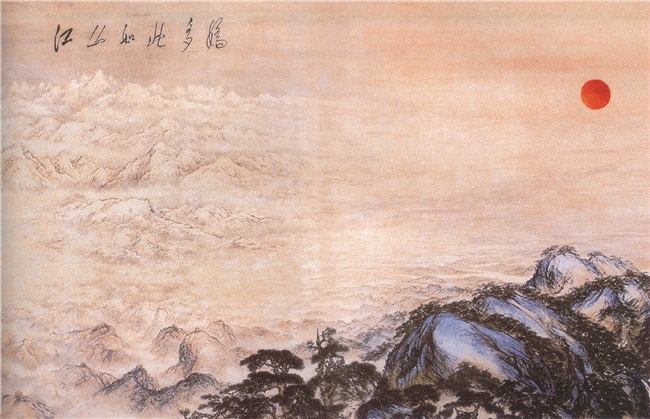

Fù Bàoshí, This Land So Rich in Beauty (co-created with Guān Shānyuè)

Scale: Monumental 9×6.5 meters

Technical Innovation: “Disheveled brushwork” evokes wind-swept snow; cinnabar dots trace the Great Wall like vital veins.

Epilogue: Millennial Continuum

From the Song’s awe toward nature, through the Ming’s liberation of individuality, to the Qing’s shattering of conventions, culminating in the modern synthesis of traditions—the millennium-long evolution of Chinese painting unfolds in this grand tapestry.