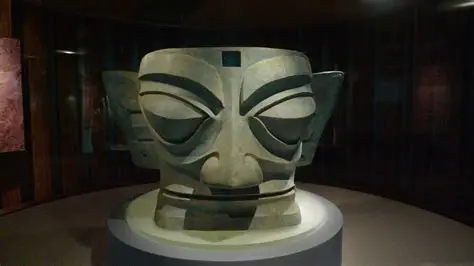

On the vast Chengdu Plain in southwestern China, an ancient and mysterious civilization has awakened…

The Architectural Context of Japanese Temples and Chinese Culture: Traces of a Millennium of Exchange

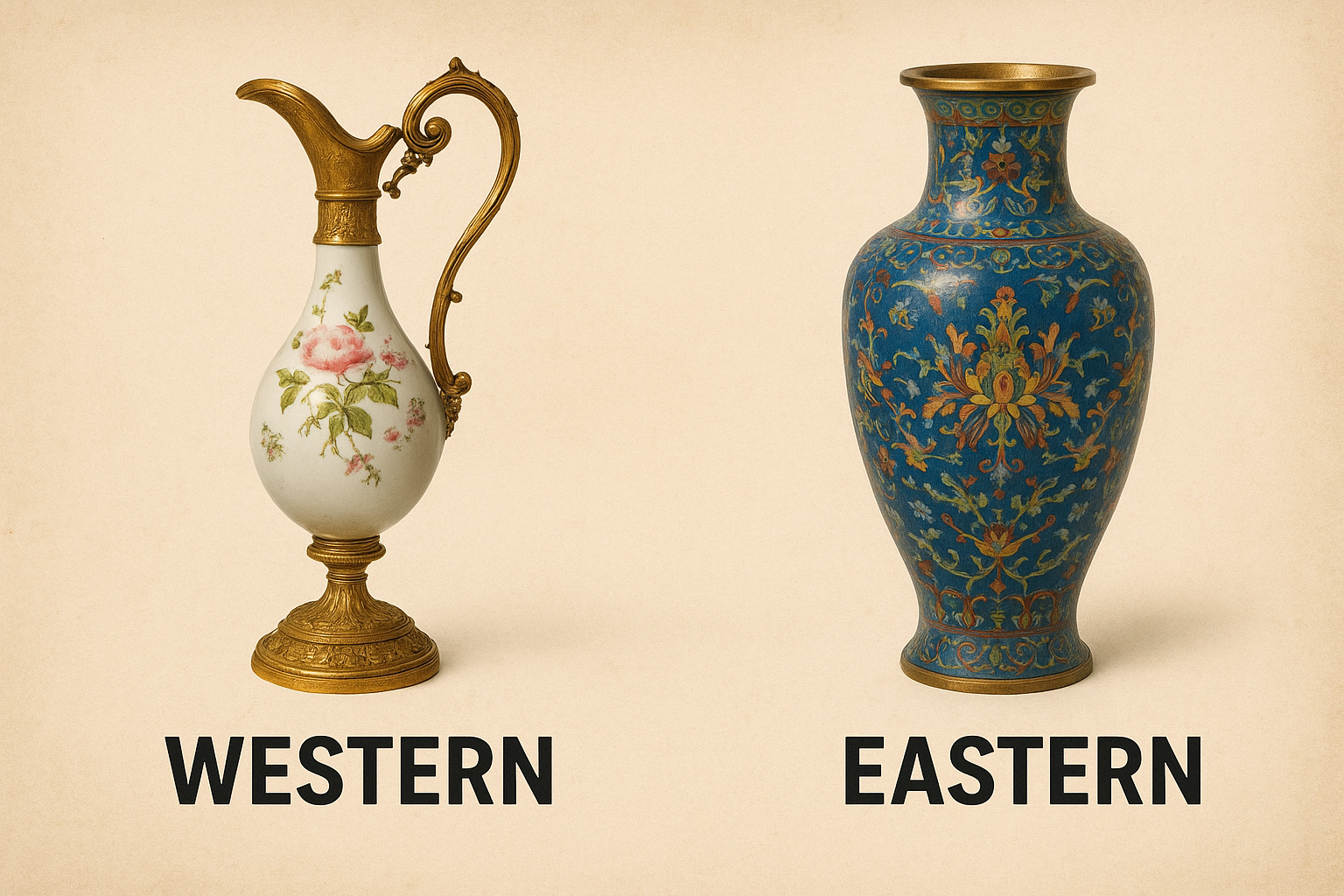

Within the East Asian cultural sphere, Japanese temple architecture is not only a physical embodiment of religious belief but also a profound testament to the long history of cultural exchange between China and Japan. From the Asuka period to the modern era, the evolution of Japanese temple architecture bears the indelible imprint of Chinese cultural influence. Through the process of localization, however, it has developed a distinctive architectural aesthetic and spiritual worldview uniquely its own.

1. Buddhism and Architectural Models Introduced from Tang China

Although Buddhism was first transmitted to Japan via the Korean Peninsula, its core doctrines, translated scriptures, and original architectural models all stemmed from China—particularly from the institutionalized Buddhism and palatial architectural styles of the Sui and Tang dynasties.

In the 7th century, Japan dispatched official missions to the Sui and Tang courts (known as Kenzuishi and Kentōshi) to study Chinese political systems, religious thought, and architectural techniques.

Famous temples from the Nara period—such as Tōdai-ji, Hōryū-ji, and Tōshōdai-ji—were modeled directly on Tang dynasty temples. They adopted symmetrical layouts, multi-eaved roofs, timber frame structures, and complex dougong (bracket) systems, conveying a sense of solemnity, grandeur, and structural stability.

2. Temple Layouts and the Chinese Concept of Sacred Space

Chinese Buddhist temples emphasize axial symmetry, reflecting both Confucian notions of hierarchical order and the Buddhist cosmological worldview. In its early stages, Japan fully adopted this spatial logic.

For instance, Hōryū-ji in Nara follows the traditional Chinese temple layout of a trinity composed of the Main Hall (Kondō), Lecture Hall (Kōdō), and Pagoda (Tō), symbolizing the transmission of the Dharma and the sequential path of spiritual cultivation.

This spatial configuration embodies a journey from the secular to the sacred, from the outer to the inner realms—an architectural expression of spiritual transformation profoundly influenced by Chinese philosophical thought.

3. The Transmission of Zen and the Evolution of Minimalist Aesthetics

During the Kamakura period (late 12th to 14th century), Zen Buddhism was introduced to Japan from Song dynasty China, bringing not only new religious philosophies but also fresh architectural forms and aesthetic sensibilities.

Temples such as Kennin-ji, Nanzen-ji, and Myōshin-ji in Kyoto were modeled after Song dynasty Zen temples. They featured more minimalist spatial layouts, rock gardens (kare-sansui), and elements of dry landscape design, all reflecting Zen ideals of impermanence (mujō) and serene emptiness (kūjaku).

These stylistic elements, deeply rooted in Song literati aesthetics, gradually evolved into Japan’s distinctive wabi-sabi aesthetic—marked by simplicity, imperfection, and quiet elegance.

4. Architectural Craft and Structure: The Fusion and Reinvention of Chinese and Japanese Techniques

Japanese temple architecture widely employs timber frame construction, a tradition that can be traced back to Chinese wooden architectural techniques from the Han to Tang dynasties. During the peak of Japan’s Kentōshi (envoys to Tang China) missions in the Asuka and Nara periods, Japanese scholars and craftsmen directly absorbed Chinese methods such as mortise-and-tenon joinery, dougong (bracket sets), and ridge design.

However, as construction adapted to Japan’s distinct climate, available materials, and aesthetic preferences, local innovations emerged. These included more prominently upturned eaves, softer rooflines, and simplified structural forms.

Such adaptations gave Japanese temples a dual character: while preserving the structural integrity and grandeur of Chinese influence, they also embodied the elegant restraint and spiritual ambiance unique to Japanese architectural identity.

5. Continuity and Re-Creation Within a Cultural Context

It is worth noting that Japanese temples are not merely places of religious practice—they are holistic spaces encompassing art, literature, and landscape design. Since the Heian period, temples have served as venues for the aristocracy and literati to gather, create, and cultivate the self. This cultural phenomenon directly continues the Chinese Tang and Song tradition of the literati retreating into temples.

Moreover, temples became fertile ground for the development of traditional arts such as the tea ceremony and ikebana (flower arrangement), highlighting how the spiritual and cultural essence of Chinese civilization was reconstructed and transformed within the spatial and aesthetic framework of Japanese temples.

Conclusion: A Historical Architectural Dialogue

Japanese temple architecture is not the product of a single civilization, but rather the cultural crystallization of a thousand years of interaction between China and Japan. In form and spirit, in technique and aesthetics, Chinese culture provided a profound foundation for the development of Japanese Buddhist temples. In turn, Japan, through its delicate process of localization, breathed new life and soul into these architectural forms.

This architectural dialogue across the sea not only preserves a rich legacy of historical transmission, but also offers a valuable lens through which we can understand the exchange and integration that have shaped East Asian civilization.