Titian (c. 1488-1576) was a prominent figure of the Venetian school during the late Italian…

Before the Rock Awakes: Sculpture, Humanity’s Earliest “Declaration of Existence”

Have you ever wondered what change occurred in the world when the first sculpture was born from the hands of early humans?

It might have happened on some evening thirty thousand years ago. A Paleolithic ancestor, while handling a smooth piece of flint, suddenly felt its natural curves under their fingertips—how much it resembled the rounded abdomen that nurtures life. And so, with another stone, they began to carefully chip and grind away.

As the last fragments fell, a small stone figurine known as the “Venus of Willendorf” awoke in the flickering light of a campfire. She was full and rounded, bearing no relation to any later aesthetic standards, yet she embodied humanity’s earliest awakening to life, fertility, and existence itself.

This is not art, but sorcery. At the moment of the Venus’s birth, the origin of sculpture was anchored in the deepest layers of the human spirit: we sought to give visible form to invisible forces, to solidify flowing fears and desires into a tangible “reality.”

The ancient Greeks elevated this yearning to its first peak. For them, sculpture was a battleground where divinity and reason converged. How could a block of cold marble transform into a sun-warmed Apollo? The answer lay in the delicate balance between “imitating nature” and “transcending nature.” The sculptor Praxiteles dared to depict the goddess Aphrodite standing nude—not as an act of blasphemy, but as a declaration: the perfect human form was the very dwelling place of the divine.

In the Middle Ages, sculpture moved from temples into churches, and stone began to “speak.” The column statues of Chartres Cathedral stood solemn and majestic, each fold of drapery a stairway to heaven. Sculpture was no longer an independent object of aesthetic contemplation; it became a Bible in stone, a sacred illustration for those who could not read.

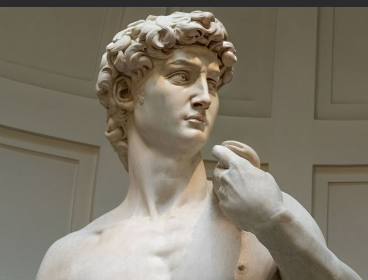

Then came the Renaissance and the “awakening of humanity.” Michelangelo entered the quarry, claiming he merely “freed the human form trapped within the stone.” His David, muscles taut and gaze piercing, was no longer a vessel for divinity but the perfect incarnation of human will and strength—a block of stubborn stone, thus sublimated into an eternal symbol of humanism.

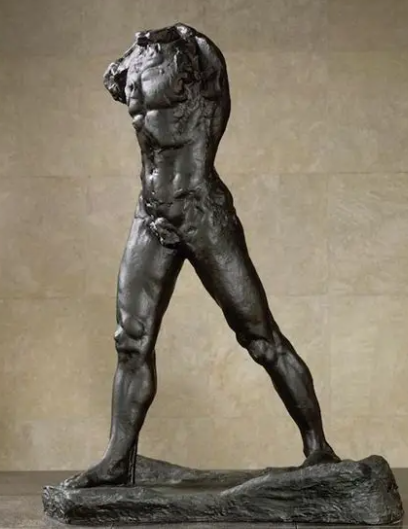

From the passionate turmoil of the Baroque era (Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa seemed to make stone itself revel in rapture) to Rodin’s infusion of the philosophy of the “unfinished” into clay (his Walking Man lacks head and arms, yet strides forth with all the solitary courage of humanity), the history of sculpture is, in truth, a history of humankind continuously redefining “existence.”

Why do we sculpt?

Perhaps it is because we fear transience too deeply. Time is formless, life is fragile, love and faith are elusive. And so, we turn to metal, stone, clay, and wood—forging fleeting epiphanies, collective beliefs, and individual passions into form, attempting to cast an anchor of permanence into the relentless current of impermanence.

Next time you pass by a sculpture—whether a hero in a square or an abstract shape in a gallery—pause for a moment. Touch its cool surface, and imagine that before it became “art,” it was merely a silent stone in the depths of a mountain. Only when human hands poured a fragment of soul into it did it gain another kind of life.

The origin of sculpture begins with the simplest of acts: a person shaping material in their hands into something meant to outlast themselves. It is our earliest courage against time, and our most romantic rebellion.