On the vast Chengdu Plain in southwestern China, an ancient and mysterious civilization has awakened…

In the Warmth of Hands, Seeing Time: The Slow Beauty of Japanese Crafts

In today’s “faster is better” era, slowing down has almost become a luxury.

Every day, we are surrounded by countless machine-made products—homogeneous in appearance, rapidly replaced, yet rarely inspiring genuine emotional connection.

But in Japan, there is a group of people who still use their hands and time to protect these nearly vanishing “slow things”—

They are dyers, papermakers, potters, coppersmiths, swordsmiths; they don’t rush time, only mastery.

Their works are more than just objects; they are cultural reflections and distilled philosophies of life.

Today, this article will take you into the world of Japanese traditional crafts and explore why, even in our highly technological era, these crafts still deserve attention, respect, and a renewed embrace.

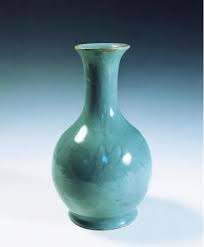

1. What Are Japanese Traditional Crafts?

In Japan, these creations share a common name: “伝統工芸品 (dentō kōgeihin)” — traditional crafts.

This is not a vague concept but a designation officially recognized, protected, and promoted by the government as national cultural assets.

Currently, over 230 types of crafts have been designated across Japan, involving ceramics, textiles, lacquerware, woodworking, metalwork, paper, bamboo, glass, swords, and more.

For example:

Nishijin weaving in Kyoto (so delicate that tens of threads fit within one millimeter)

Kanazawa gold leaf (producing 99% of the world’s gold leaf)

Tsugaru lacquerware in Aomori (involving up to 48 processes and over six months of work)

Izumo paper in Shimane (paper that can last a thousand years without yellowing)

These crafts are not merely “techniques,” but the crystallization of a region’s history, natural resources, and aesthetic philosophy.

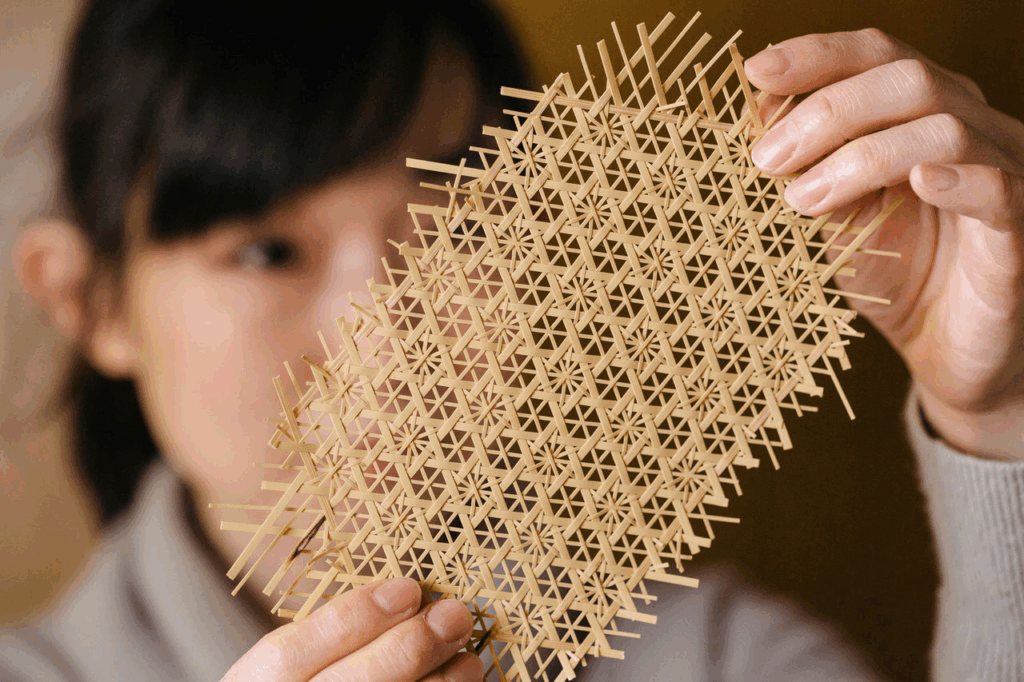

2. Why Are They Called “Objects of Time”?

Visitors often ask artisans during factory tours:

“Why spend months making a single bowl? Machines can do it faster and cheaper.”

The craftsmen just smile and keep working.

For them, speed is never the measure of a piece’s value.

What matters is:

Has the wood been dried through three winters?

Has the paper pulp been beaten to the finest fibers?

Has the lacquer dried too slowly on a rainy day?

Was the forge temperature off by five degrees when hammering the blade?

They know the warmth of the hands can be imprinted on the object.

A lacquer bowl requires dozens of layers of painting, drying, polishing, and repainting. Seemingly plain, yet it radiates a gentle aura in the light — something machines will never replicate.

They believe objects have a soul, and craftsmanship can connect to the divine.

3. Are Young People Still Willing to Learn These “Old Crafts”?

This is a challenge facing the craft industry — older craftsmen are aging, and fewer young people are willing to learn.

After all, in this fast-paced, sometimes indifferent era, who wants to spend a lifetime dyeing just one color? Who wants to polish the edge of the same cup day after day?

Yet surprisingly, some young people are “returning.”

Architects resign to study woodworking in their hometowns to protect local cedar craftsmanship;

Graphic designers collaborate with dyers to transform traditional patterns into modern wallpaper;

University students build online platforms to help endangered workshops reach global markets.

They are not mere apprentices but “translators” between culture and the times.

They tell traditional skills, patterns, and materials in new languages, so more people can understand, use, and love them.

Thus, crafts are no longer museum relics or luxury collectibles.

They become part of your life:

A handmade washi notebook on your desk;

A Mino ware cup for daily coffee;

A phone case decorated with century-old gold leaf craft.

The boundary between life and beauty quietly draws closer through these objects.

4. Tradition and the Future: Not Opposition, But Coexistence

The value of traditional crafts lies not in “clinging to the past” but in “connecting to the future.”

In Japan, we see:

Technology + Handcraft: University of Tokyo researches AI-assisted forging to help swordsmiths judge fire temperature;

Design + Craft: Brands like MUJI, BEAMS, and TSUBAME collaborate with local workshops to infuse old crafts into modern products;

Culture + Tourism: Regions offer “craft experience tours,” where visitors participate in making lacquerware, pottery, and textiles, drawing closer to the craft.

This is not compromise but evolution.

After all, tradition is not a museum “fossil” but a flowing river.

We don’t have to live as in the past, but we can learn from it how to live better.

5. In Conclusion: Why Do We Still Need “Slow” Things?

Some say the charm of crafts lies in their “imperfection.”

It’s the traces of the hand that give them character;

It’s because each piece is never exactly the same that they deserve to be cherished.

In this era of fast consumption and fast replication,

Perhaps what we need is not more “new” things,

But more “old crafts” worth slowly feeling and understanding.

Not because they are nostalgic, but because they are real.

Not because they are rare, but because they have warmth.

May we no longer just pursue “the fastest arrival,”

But start to appreciate “the most beautiful process.”

May we, through these carefully made objects,

Rediscover our relationship with time, the world, and ourselves.